TOPIC DETAILS

What is Space Situational Awareness?

Space situational awareness (SSA) is the practice of characterizing, tracking, and predicting the future position of objects in space around Earth. Governments, companies, and institutions engage in SSA to understand the growing number of space assets in Earth’s orbit and in the space impacted by the gravity of both the Moon and Earth, called cislunar space.

The first step in establishing space situational awareness is to utilize ground-based observations to identify and track near-Earth objects. This space surveillance data is then used to create a digital representation of each space object. Finally, orbital mechanics and other physics are applied to predict how gravity and other forces determine each object's orbit over time.

Why is Space Situational Awareness Important?

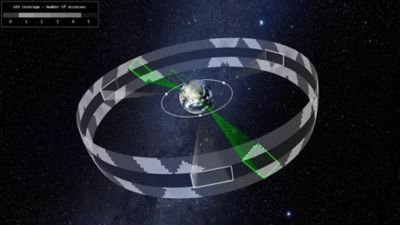

Inspection of regions of the GEO satellite belt from facilities on the surface of the Earth as well as in low-Earth orbit.

The primary goal of obtaining space situational awareness is to prevent collisions between spacecraft and space debris. Secondary objectives include planning the reentry of retired or defunct space vehicles and analyzing the fragments created by collisions, on-orbit explosions, or hostile acts.

Space situational awareness is also the foundational data and toolset for space traffic management systems. It not only prevents unwanted interaction but also helps in proactively managing the orbits of controllable objects.

Space agencies, militaries, and satellite operators develop SSA capabilities to protect their space-based hardware, maintain functionality for as long as possible, and avoid causing harm to both other space vehicles and people and infrastructure on the ground during reentry. These entities not only want to protect their significant investment, but they also want to maintain the science, communications, and Earth observation capabilities that those assets deliver, which are crucial to everyday commerce and national security.

Since Russia launched Sputnik in 1957, the European Space Agency (ESA) calculated that governments and corporations have launched more than 21,600 satellites into Earth’s orbit, with more than 14,200 still operational in 2025. Launch hardware and the debris from more than 650 collisions add to the 54,000 objects in orbit that are over 10 centimeters long, along with millions of smaller fragments.

Number of pieces of debris in low Earth orbit (LEO) arranged by size

Even though near-Earth space is vast, the chance of collision is statistically significant because objects in orbit are moving at very high speeds on different trajectories, and many satellites must occupy or pass over the same locations on the Earth’s surface. The importance of SSA in space operations, economics, and politics has grown due to the near-exponential increase in trackable objects, the growing reliance on space-based communication and observation, its strategic role in national security, and increased access to space by non-allied governments.

The 3 Components of Space Situational Awareness

The foundation of SSA is computational orbital mechanics, which utilizes both classical and relativistic physics to predict the effects of gravity on orbits. Gravitational forces from the Sun, Earth, and Moon play the most significant role in these calculations.

To correctly track and predict space objects, SSA systems need to include three components in their calculations.

1. Characterization of Space Objects

The first component of SSA is characterizing objects in orbit. SSA systems use ground-based radar and optical telescopes, collectively referred to as space surveillance and tracking, to gather this data. Trackers use the location and velocity of an object to determine its mass. They also use internal and external sources to identify the object and catalog any available geometric or operational features.

Tracking space objects is not a one-time task. Many objects can change trajectory, and small forces like drag and pressure from space weather can unpredictably change orbits. Beyond manmade objects, SSA systems also track near-Earth asteroids.

2. Tracking or Predicting Space Debris

Understanding space debris is the second component of SSA. Explosions, mechanical failures on a spacecraft, and collisions between objects can create debris. Because the fragmentation caused by these events creates small particles moving in multiple directions, advanced SSA systems capture the characteristics of the space debris and predict what the debris field looks like from actual or potential collisions.

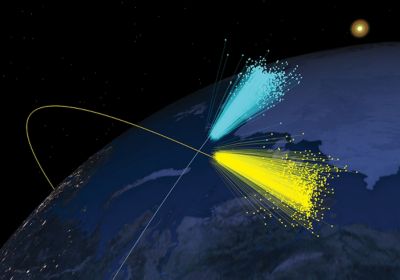

Iridium 33-Cosmos 2251 satellite collision reconstructed from measured data using Ansys Systems Tool Kit (STK) software, which reflects notional debris dispersion

3. The Impact of Space Weather

The third component in space situational awareness is taking space weather into consideration. Solar storms generate radiation that can create disturbances and interfere with satellite trajectories. During such an event, charged particles can affect the density of Earth’s upper atmosphere in ways that create drag on the satellite, which can affect orbit trajectories. SSA implementations need to constantly consider solar radiation and forecast the effect of space weather in their calculations.

Other Factors That Impact Space Situational Awareness

Another factor that influences SSA tracking and predictions is drag from the Earth’s atmosphere (although very thin at orbital levels) on spacecraft in near-Earth space, especially in low Earth orbit (LEO). Drag is also a significant factor in reentry calculations.

Similar to the forces imparted by solar radiation, reflected heat and visible light from Earth (albedo) will also cause perturbations to the spacecraft motion, varying as the object changes its position relative to the Sun and Earth.

Another consideration is the failure of orientation systems — which usually include a set of gyroscopes — in satellites. The orientation of a spacecraft relative to the Sun and Earth is important because it can affect how much radiation pressure and drag the object experiences.

Challenges in Maintaining Space Situational Awareness

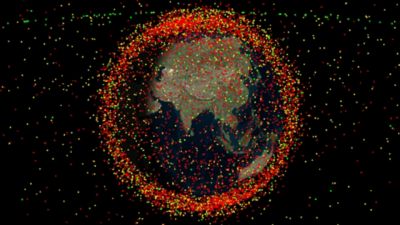

A representation of objects in near-Earth space based on cataloged orbital data. Pixel point depiction limitations convey greater than actual density, although the implied situation is consistent with current trends.

Establishing and maintaining a space situational awareness system is a significant undertaking. In the past, government agencies have implemented most SSA systems. The United States maintains several SSA systems through the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Space Force, the U.S. Air Force, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for commercial efforts, with the Space Surveillance Network (SSN) serving as the primary system.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is the primary administrator of Europe’s Space Safety Programme. Other countries have similar systems to support their space activities or partner with one of the larger systems. With the growth of commercial spaceflight, several commercial SSA solutions are currently available or under development.

Here are some of the common challenges these teams face in maintaining space situational awareness.

More and Smaller Spacecraft

The small satellite (“smallsat”) revolution, coupled with decreased launch costs, has ushered in a massive increase in spacecraft. These smaller objects are more difficult to track due to their size and sheer numbers.

Competition for Prime Geography

Satellites are not distributed evenly around Earth. To remain fixed relative to the Earth’s surface, satellites in geosynchronous orbit (GEO) must share the same altitude. In addition, many operators want to position their spacecraft over the same regions. Because of this, GEO is an increasingly crowded place. Satellites in low Earth orbit have the same problem because many missions seek to observe or receive signals from the same locations.

Cost-Effective and Accurate Observation

Space surveillance networks are expensive to build and maintain, requiring the latest in optical and radar sensing technology. As the complexity of the orbital situation increases, the cost of these systems also goes up.

Data Management and Storage

The amount of data collected for each object in space is significant. This is not just because of the increase in spacecraft and debris levels, but also because SSA data spans many years of observation.

Visualization

A growing challenge is presenting SSA data in an informative and actionable way. The volume of space that SSA teams monitor is massive, existing in three dimensions and covering an increasing number of objects.

Prediction

SSA systems need to predict future orbits, identify potential threats, and model space debris when a collision event occurs. Engineers also use SSA systems to plan reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere or dispose of defunct spacecraft by moving them into stable orbits.

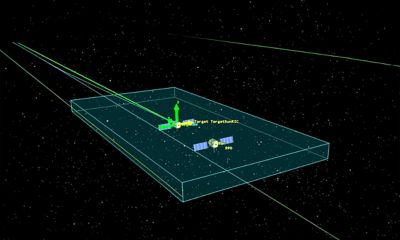

A simulation showing a potential collision between two satellites

Meeting Challenges in Space Situational Awareness

Organizations involved in SSA have several tools at their disposal to address the challenges they face.

Policy and Strategy

Human solutions for SSA revolve around policy and strategy. Many international standards exist, with most space-capable nations agreeing to them in principle. These include the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the Liability Convention of 1972, and the Registration Convention of 1976.

More recently, groups have sponsored guidelines and strategies that ask member states to cooperate and act responsibly. These agreements encourage:

- Limiting debris

- Minimizing on-orbit breakup

- De-orbiting spacecraft at the end of their mission

- Implementing collision avoidance technology

- Avoiding the intentional destruction of objects in space

Software and Hardware

The technical solutions consist of robust software and hardware systems that gather information, implement space traffic management (STM) tools, and use space domain awareness (SDA) solutions to support national security issues.

Hardware solutions utilize advanced computing power, including high-speed memory, GPUs, and cloud computing, to handle the massive amounts of data and calculations required. Hardware also supports the sensors used in tracking systems. Advances in both on-orbit and ground-based optical sensors and radar systems are making strides in providing more accurate and timely information. Engineers are utilizing tools like Ansys HFSS software to design more effective antennas and Ansys Zemax OpticStudio software to enhance camera performance.

On the software side of the toolset, the key to addressing SSA challenges is to have a robust and flexible platform on which to build SSA system software. Solutions like Ansys Systems Tool Kit (STK) software provide a physics-based foundation that accurately models and efficiently predicts the behavior of objects and debris in space. Or, a platform like Ansys Orbital Determination Tool Kit (ODTK) software can help predict future spacecraft behavior from tracking data. With a flexible and powerful platform to build on, each SSA team can develop a software solution tailored to their specific needs.

Best Practices for Establishing Space Situational Awareness

The number of objects in Earth’s orbit from launch and debris will continue to increase as humans expand beyond Earth into cislunar space and beyond. Decades of building space situational awareness have provided the aerospace industry with lessons and best practices to make our future space environment safer.

1. Follow the Rules

The first step in SSA is for spacecraft designers and operators to follow established policies and guidelines for coexistence in orbit.

2. Invest in Tracking Technology and Share Data

Because high-quality output depends on high-quality input, maintaining SSA is highly dependent on the fidelity and timeliness of tracking data. Data sharing also increases the capabilities of SSA systems.

3. Leverage Improvements in Computational Capabilities

Managing the significant amount of data produced by space surveillance requires higher speeds and capabilities in computer hardware as well as algorithmic improvements. The statistical capabilities of quantum computing have the potential to revolutionize SSA.

4. Implement Advances in Data and Predictive Analytics

Ultimately, SSA is centered on predictive and data analytics, which are grounded in physics-based modeling. Operators can enhance SSA through advancements in standard data analytics, as well as in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI).

5. Build High-Fidelity Physics-Based Digital Representations

The real power of SSA in predicting and avoiding potential threats comes from the use of digital mission engineering (DME) based on high-fidelity digital representations of the environment around Earth. This includes the key components of spacecraft, debris, and space weather, plus all other factors that affect the position of an object in orbit over time.

Related Resources

现在就开始行动吧!

如果您面临工程方面的挑战,我们的团队将随时为您提供帮助。我们拥有丰富的经验并秉持创新承诺,期待与您联系。让我们携手合作,将您的工程挑战转化为价值增长和成功的机遇。欢迎立即联系我们进行交流。