-

-

Accédez au logiciel étudiant gratuit

Ansys donne les moyens à la prochaine génération d'ingénieurs

Les étudiants ont accès gratuitement à un logiciel de simulation de classe mondiale.

-

Connectez-vous avec Ansys maintenant !

Concevez votre avenir

Connectez-vous à Ansys pour découvrir comment la simulation peut alimenter votre prochaine percée.

Pays et régions

Espace client

Support

Communautés partenaires

Contacter le service commercial

Pour les États-Unis et le Canada

S'inscrire

Essais gratuits

Produits & Services

Apprendre

À propos d'Ansys

Back

Produits & Services

Back

Apprendre

Ansys donne les moyens à la prochaine génération d'ingénieurs

Les étudiants ont accès gratuitement à un logiciel de simulation de classe mondiale.

Back

À propos d'Ansys

Concevez votre avenir

Connectez-vous à Ansys pour découvrir comment la simulation peut alimenter votre prochaine percée.

Espace client

Support

Communautés partenaires

Contacter le service commercial

Pour les États-Unis et le Canada

S'inscrire

Essais gratuits

ANSYS BLOG

September 20, 2023

What Are PFAS “Forever Chemicals”?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of synthetic substances that have desirable properties but can cause negative impacts to human health and the environment. With diverse uses in a broad range of industries, PFAS are in everything from cookware and airplane de-icers to circuit boards and pacemakers.

Many countries are starting to regulate the manufacture and use of PFAS in products, and some manufacturers have announced they will stop producing them altogether. So, what happens to the companies that rely on PFAS to make their products? How do they know if PFAS are even in their materials and products? And how will they know what to replace PFAS-containing materials with?

Pacemakers are often manufactured with PFAS containing materials due to their water repellant properties.

A Brief History of PFAS

PFAS are a group of thousands of synthetic substances. PFAS were first created in the 1930s, but development increased in the late 1960s after a fire aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier. Afterward, manufacturers used PFAS in aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) — a foam mixture that extinguishes fire. AFFF is still used to put out fires on ships, airplanes, and airports.

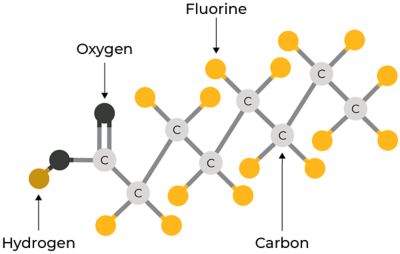

Today, there are more than 12,000 registered PFAS substances. Because PFAS substances have a chain of linked carbon and fluorine atoms, these chemicals do not degrade easily in the environment and are colloquially called “forever chemicals.” The estimated half-life of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) has been reported as >41 years but for complex PFAS substances with longer chains, half-lives of over 1,000 years in soil have been estimated. In humans, the half-life for PFOS has been estimated as 4.8 years.

Molecular structure of a typical PFAS substance

Preliminary evidence of PFAS toxicity was available as early as the 1960s, and animal tests conducted by PFAS producing companies in the 1970s concluded that PFOS and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) should be regarded as toxic. In 1998, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was first alerted to the risks associated with PFAS and a year later PFOS contamination was appearing in blood donations. In 2005, the U.S. EPA concluded that PFOA is a likely human carcinogen, a finding supported by other regulatory bodies.

Many PFAS have been found in the blood of people and animals all over the world, PFOS and PFOA are estimated to be in the blood serum of more than 98% of Americans, and they are present at low levels in different foods and the environment due to their widespread use. Studies have shown that exposure to certain PFAS can be harmful to human health, with risks including reproductive effects, developmental delays, cancer, reduced immune responses, and more.

How are PFAS Being Regulated?

Because of the associated risks to human health and the environment, countries and regulatory bodies around the world are enforcing regulations and restrictions around the use of PFAS in different products.

The European Union’s (EU) Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) has already placed some restrictions for subgroups of the PFAS family: PFOS, PFOA, and C9-C14 perfluorinated carboxylic acids. Others have also been identified as substances of very high concern (SVHC) under EU REACH: perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) and its salts, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) and its salts, amongst others.

However, the most far-reaching is the "universal" PFAS restriction, detailed in the Annex XV Restriction Report, the proposal of which was published in February 2023. The restriction “is tailored to address the manufacture, placing on the market, as well as the use of PFASs as such and as constituents in other substances, in mixtures and in articles above a certain concentration” and will likely come into force in 2025 or 2026. The restriction covers all uses of PFAS, unless otherwise noted in the proposal, and it’s still unknown whether use-specific, time-limited exemptions will be allowed.

In April 2023, the EPA submitted a proposal for a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) to establish legally enforceable levels for six PFAS substances in drinking water — including PFOS, PFOA, perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA), PFHxS, and PFBS. The proposed regulation would hold public water systems accountable for:

- Monitoring for these PFAS.

- Notifying the public of the levels of these PFAS.

- Reducing the levels of these PFAS in drinking water if they exceed the proposed standards.

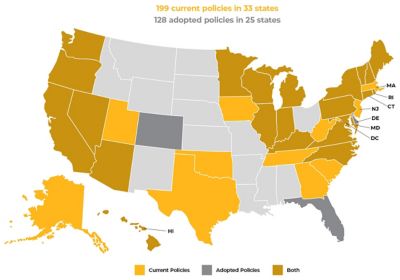

There are currently no federal regulations of PFAS in the U.S., but individual states are taking action to regulate this group of substances. California, Maine, and New York already have restrictions in place for certain uses — such as food packaging — and many states such as Washington, Minnesota, Vermont, Maryland, Colorado, Connecticut, and Hawaii are slated to introduce restrictions in the coming years.

U.S. states with current and adopted PFAS policies.

Finding Solutions to Identify and Avoid PFAS

With impending restrictions and regulations, sustainability efforts, and the potential for obsolescence, many companies are taking a proactive approach to reduce or eliminate their use of PFAS. But because there are so many kinds of chemicals that qualify as PFAS, it can be hard for companies to know if their products contain PFAS-containing materials.

Using a materials data management solution enables companies to identify and control the materials used in their products. Having this information on hand can facilitate conversations between materials decision stakeholders in procurement, regulatory, engineering, design, and manufacturing.

Companies can also integrate across computer-aided design (CAD), computer-aided engineering (CAE), and product life cycle management (PLM) systems to save time, drive innovation, cut costs, and eliminate risk. Knowing PFAS will be against regulations, companies can use these solutions to determine if their products contain PFAS or any of their variants.

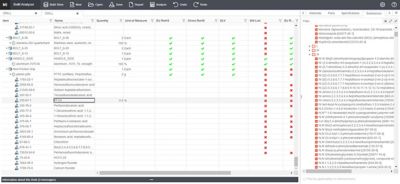

In preparation for the impending restrictions, Ansys is identifying substances that meet the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) PFAS definition and adding them to Granta MI, Ansys’ material data management solution. By including CAS numbers, trade names, and synonyms, the identification and screening of materials, parts, and specifications that may contain PFAS is easier.

Even if the precise material composition is not available, the Ansys suite of 4,200+ generic engineering materials provides insight into restricted substances commonly found in these materials and how they are likely to be impacted. Users can then easily manage their own data on materials, suppliers, legislations, treatments and restricted substances enterprise-wide, for an ‘authoritative source of truth’ for materials. Combining all this together with tools like bill of materials (BoM) analyzer, an entire product can easily be analyzed for the presence of a restricted substance risks, including PFAS.

Bill of materials (BoM) analyzer

Once it is determined that a product contains PFAS, companies will need to find replacement materials. Replacing a material in a product isn’t as easy as it sounds — the material has to meet certain economic and performance requirements — mechanical, thermal, durability and much more. Additional regulations may even apply such as healthcare and food processing. By integrating restricted substances data and BoM analysis capabilities with leading engineering systems and material selection capabilities, companies are able to choose suitable, compliant alternatives.

Register for our upcoming webinar "Ansys 2023 R2: How to Prepare for New PFAS Regulations in 2024" to learn more about how the Ansys Granta MI restricted substances database can help you remove PFAS from your products.